Blurring the Lines: Why Sequoia's Evergreen Fund May Disappoint

On October 26, venture capital (VC) firm Sequoia announced that it was launching an open-ended fund (“The Sequoia Fund”), through which all its investments, both public and private, would flow. The decision would thus end the firm’s dependence on the traditional 10-year VC fund cycle which it likened to the “business equivalent of floppy disks.” With it came many immediate reactions, some stating it was the end of the VC model as we knew it and that other established VCs would surely follow.

With an open-ended (i.e., evergreen) fund, there is no defined term in which Sequoia must liquidate its holdings and distribute proceeds to its investors:

“Moving forward, [Sequoia] LPs will invest into The Sequoia Fund, an open-ended liquid portfolio made up of public positions in a selection of our enduring companies. The Sequoia Fund will in turn allocate capital to a series of closed-end sub funds for venture investments at every stage from inception to IPO. Proceeds from these venture investments will flow back into The Sequoia Fund in a continuous feedback loop. Investments will no longer have ‘expiration dates.’ [Sequoia’s] sole focus will be to grow value for [its] companies and limited partners over the long run.”

Excluding the flows into and out of its sub-funds, The Sequoia Fund will essentially be operating as an actively managed fund of publicly traded investments. Citing a few examples of hugely successful companies in which Sequoia was an early investor (in fact, there are quite a few), the thought is that if Sequoia hadn’t been required to liquidate or distribute shares post-IPO lockup, investors would have been exponentially better off.

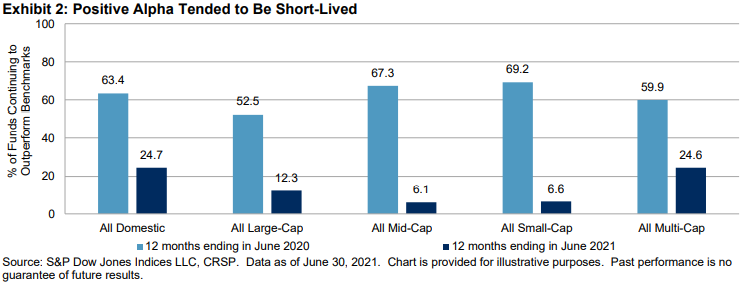

As strong believers in behavioral finance, this decision by Sequoia checks a few of those biases that end up crippling active managers (overconfidence and regret aversion, to name a few). While top-quartile venture fund managers tend to continue outperforming with subsequent funds, the performance persistence does decline in the long run. But it’s even worse for active managers of public market investments as “regardless of asset class or style focus, active management outperformance is typically short-lived.”

For firms like Sequoia, performance persistence in the VC world is at least partially attributed to its reputation which enables it to continuously attract high-quality companies and negotiate better priced deals. However, the advantage of this reputational feedback loop would disappear post IPO as Sequoia becomes subject to the whims and efficient pricing of the public markets. Axios noted that, an “internal review of distributions over the past 15 years shows that had Sequoia held onto shares for just 12 additional months, it would have resulted in over $8 billion in added returns.” No small sum, but past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Per research conducted by NASDAQ on IPOs between 2010 and 2020, performance varies significantly and even more so the longer the timeframe. Per the chart below, most companies one year after IPO are either outperforming or underperforming the market by more than 10%. But even more alarming is that most companies had underperformed their respective index return and 50% had underperformed by more than 10%.

“The popular view of venture investing is that it is about picking good companies, because that’s what’s important with public equities. But you can’t apply the logic of public equity markets, where by definition anyone can invest in any stock. Success in VC is probably 10% about picking, and 90% about sourcing the right deals and having entrepreneurs choose your firm as a partner.”

While some LPs may applaud Sequoia’s move because they prefer delegating all buy, hold, and sell decisions to Sequoia, blurring the lines between what makes a private market and public market manager successful may only lead to disappointing results. With the Sequoia Fund only time will tell.

Best Regards,

Adam J. Packer, CFA®, CAIA®

Chief Investment Officer | SineCera Capital